William has been on the run since he gave a 19 page report of the safety problems with Trident Nuclear weapons. Wills report echos the revelations of less well know whistle-blowers who also had to escape the UK for fear of reprisals.

The Courage Foundation has opened an emergency fund for Trident whistleblower William McNeilly’s defence costs.

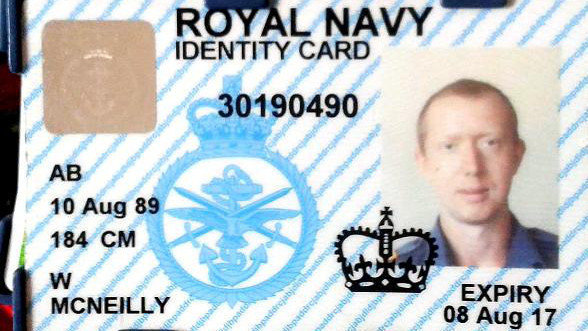

Able Seaman William McNeilly is a 25-year-old British Engineering Technician Weapons Engineer Submariner who has blown the whistle on major safety risks and cover-ups within the British Royal Navy’s Trident nuclear weapons programme, stating, “We are so close to a nuclear disaster it is shocking, and yet everybody is accepting the risk to the public.”

William McNeilly released a 16-page report to WikiLeaks, who published the original in full. The report draws on McNeilly’s experience in the Royal Navy to detail security lapses, safety hazards and a culture of secrecy and cover-up. In particular, McNeilly describes surprisingly weak security around the UK’s Trident nuclear submarine base, writing that “it’s harder to get into most nightclubs than it is to get into the [restricted] Green Area.”

McNeilly has turned himself in to police and is now being held in Royal Navy custody at an undisclosed location, where he faces potential prosecution. Whilst it is yet unclear what charges McNeilly will face, he is in military custody and the UK has a number of military charges that, like the Espionage Act in the United States, do not offer defendants the chance to make a public interest defence.

Regarding his reasons for acting as he has done, McNeilly explained the difficulty of achieving results through regular channels: “I’m releasing this information in this way because it’s the only way I can be sure it gets out. I raised my concerns about the safety and security of the weapon system through the chain of command on multiple occasions. My concern couldn’t have been any clearer.”

The Courage Foundation is taking McNeilly on as an emergency case, providing a defence fund immediately for the public to donate to, ensuring its possible for him to mount the best defence from the start.

Britain’s nuclear deterrent, which is based at Falsane in Scotland, has been the subject of increasing domestic controversy over recent months as the latest possible date for a political decision on its renewal draws near. The Scottish National Party, whose MPs won 56 of Scotland’s 59 parliamentary seats in the recent General Election, is strongly opposed to a Trident replacement being commissioned.

Among the most startling of McNeilly’s revelations include the fact that three missile launch tests failed, missile safety alarms were ignored, torpedo compartments were flooded and bags were not properly checked for security risks. He also claims that HMS Vanguard crashed into a French submarine in February 2009. McNeilly says there was a “massive cover up of the incident. For the first time the no personal electronic devices with a camera rule was enforced.” At the time, the Guardian reported that “the Ministry of Defence initially refused to confirm the incident” and that Vanguard suffered mere “scrapes”, but McNeilly says one officer told him, “We thought, this is it – we’re all going to die.”

Able Seaman William McNeilly is a 25-year-old British Engineering Technician Weapons Engineer Submariner who has blown the whistle on major safety risks and cover-ups within the British Royal Navy’s Trident nuclear weapons programme, stating, “We are so close to a nuclear disaster it is shocking, and yet everybody is accepting the risk to the public.”

William McNeilly released a 16-page report to WikiLeaks, who published the original in full. The report draws on McNeilly’s experience in the Royal Navy to detail security lapses, safety hazards and a culture of secrecy and cover-up. In particular, McNeilly describes surprisingly weak security around the UK’s Trident nuclear submarine base, writing that “it’s harder to get into most nightclubs than it is to get into the [restricted] Green Area.”

McNeilly has turned himself in to police and is now being held in Royal Navy custody at an undisclosed location, where he faces potential prosecution. Whilst it is yet unclear what charges McNeilly will face, he is in military custody and the UK has a number of military charges that, like the Espionage Act in the United States, do not offer defendants the chance to make a public interest defence.

Regarding his reasons for acting as he has done, McNeilly explained the difficulty of achieving results through regular channels: “I’m releasing this information in this way because it’s the only way I can be sure it gets out. I raised my concerns about the safety and security of the weapon system through the chain of command on multiple occasions. My concern couldn’t have been any clearer.”

The Courage Foundation is taking McNeilly on as an emergency case, providing a defence fund immediately for the public to donate to, ensuring its possible for him to mount the best defence from the start.

Britain’s nuclear deterrent, which is based at Falsane in Scotland, has been the subject of increasing domestic controversy over recent months as the latest possible date for a political decision on its renewal draws near. The Scottish National Party, whose MPs won 56 of Scotland’s 59 parliamentary seats in the recent General Election, is strongly opposed to a Trident replacement being commissioned.

Among the most startling of McNeilly’s revelations include the fact that three missile launch tests failed, missile safety alarms were ignored, torpedo compartments were flooded and bags were not properly checked for security risks. He also claims that HMS Vanguard crashed into a French submarine in February 2009. McNeilly says there was a “massive cover up of the incident. For the first time the no personal electronic devices with a camera rule was enforced.” At the time, the Guardian reported that “the Ministry of Defence initially refused to confirm the incident” and that Vanguard suffered mere “scrapes”, but McNeilly says one officer told him, “We thought, this is it – we’re all going to die.”

A serving submariner has given a damning account of life onboard a Trident submarine earlier this year, describing the vessels as “a disaster waiting to happen”. William McNeilly was training to work on the Trident nuclear weapons system. He was on HMS Victorious during a three-month operational patrol which ended in April. He has published a detailed account of technical defects, security breaches and poor safety practice. The Navy has written down detailed procedures for safety and security with regard to Trident. McNeilly reveals that these rules are casually ignored on a daily basis. His account was reported by Rob Edwards in the Sunday Herald. The editorial in the paper argues that the whistleblowers report should spell the death knell for Trident.

John Ainslie, Coordinator of Scottish CND, said:

"McNeilly is a whistleblower who has revealed that there is a callous disregard for safety and security onboard Trident submarines. He should be commended for his action, not hounded by the Ministry of Defence. He has exposed the fact that Trident is a catastrophe waiting to happen - by accident, an act of terrorism or sabotage. We are told that nuclear weapons keep us safe. This report shows that Trident puts us all in great danger. McNeilly’s report would make a good script for a disaster movie. Alarms warnings are muted, safety regulations ignored, shortcuts taken, exam results falsified and major defects overlooked. What he says is credible. Official reports show that the number of safety incidents is very high and rising. McNeilly reveals what this actually means in practice."

This is the Petition organised by Scottish CND to support William and ask that he not be prosecuted. https://www.change.org/p/david-cameron-pardon-the-trident-whistleblower

Accident risk

One major concern is a fire in the Missile Compartment, which houses 8 Trident D5 missiles. Each missile contains tonnes of high explosive rocket fuel, topped with several 100-kiloton nuclear warheads. McNeilly describes an earlier incident on a Trident submarine. Toilet rolls, stacked in the Missile Compartment, caught fire. This filled several of the decks of the compartment with smoke. The crew struggled to bring the incident under control and had difficulty using their Breathing Apparatus.

Despite this earlier incident, he found that the risk of a fire in the Missile Compartment wasn’t taken seriously. A major fire in the missile area can only be brought under control by flooding the compartment with Nitrogen. However the Nitrogen cylinders were significantly below the required pressure. Restrictions on personal electronic equipment, which could trigger an electrical fire, were not enforced. McNeilly told his superiors about rubbish near the missiles, which could have caused a fire. But no action was taken.

Elsewhere on the submarine there was a real risk of an electrical fire. No attempt was made to isolate electrical equipment after a leak was detected in the riders’ mess (riders are extra personnel on the vessel). There were serious problems with condensation in parts of the submarine. A sprinkler system was accidentally activated in the torpedo room, without the electrical system having been isolated.

Crew members who work on the Trident missile system should have a thorough knowledge of CB8890, the manual for Trident safety and security. However McNeilly’s exam on the manual was a sham. Some who missed the test were allocated results at random. One of the more senior staff said that the students didn’t really need to study the whole manual.

The status of the Trident missiles is monitored at the Control and Monitoring Panel (CAMP). This should be manned at all times, but often it was not. An audible alarm on the panel was muted because it was going off repeatedly. A second recurring alarm in the Missile Control Compartment, due to a problem with power from one of the Turbo Generators, was also ignored.

One of the more hazardous operations conducted by missile engineers is the insertion of DC/AC inverters in the missiles before a patrol and their removal after a patrol. To do this they have to open a hatch in each missile tube and gain direct access to the missiles. McNeilly describes how the removal of inverters at the end of their patrol was rushed and they did not follow the written procedures.

The Navy is finding it difficult to recruit and train Trident missile engineers. The report from this submariner shows that they are placing people in positions of responsibility without adequate training and/or experience.

Other safety issues identified by McNeilly are:

•There was a list of defects on the Trident missile system on HMS Victorious and the list was almost full.

•One of the decks in the Missile Compartment was used as a gym and weights were thrown and dropped near missile equipment.

•Extra beds blocked access to DC switch boards & a hydraulics isolation valve.

•Use of banned substance in cleaning material, causing problems with fumes.

•The circumstances of the collision between HMS Vanguard and Le Triomphant in February 2009 are a closely guarded secret, but one Vanguard crew member said “We thought, this is it we’re all going to die”.

•There was an incident when a generator compartment was flooded on a submarine and this could have resulted in the loss of the vessel if it had been handled differently.

Defects on Trident submarines

McNeilly says that at the end of the patrol they tested the Missile Compensation System on HMS Victorious. This system should quickly restore the balance of the submarine after a missile is launched, to enable each subsequent missile to be fired. The test was carried out three times, and each time the test failed.

The missile hatches on the submarine are powered by the Main Hydraulic Plant. At the end of the patrol they should have tested that they would have been able to open the hatches if required. But they were unable to conduct the test because of seawater in the hydraulic system.

These two problems meant that they could not confirm that the submarine could have launched its missiles when on patrol.

McNeilly says that there was noise from the aft diving planes when the vessel submerged at the start of its patrol and that this was part of a wider issue of aft diving planes jamming. Jammed planes can lead to the loss of the submarine in an uncontrolled dive.

There were problems with the Turbo Generators, which provide the main power source, and with one of the diesel generators, which are the back-up power source. The safety of the submarine would be compromised if both sources of electrical power were lost.

In addition to these problems on HMS Victorious, McNeilly refers to defects on other submarines. He says that there are currently only two operational Trident submarines, probably due to refit and maintenance cycles, and that there are major defects on both the operational vessels.

He visited a Trident submarine in the shiplift and many of the items of equipment were tagged with red markers, either for maintenance or defects. When they were told not to touch anything in the submarine’s control room, one of the crew responded “nothing works, you can touch what you like”.

Security breaches

McNeilly revealed two major breaches of security on HMS Victorious. Despite not having DV security clearance, he was given access to Top Secret information showing where the submarine was carrying out its patrol. He also says he could have worked out the key to the Weapons Engineering Officer’s safe when he watched him enter the combination. This would have given the junior crew member unauthorised access to the trigger which launches Trident missiles. In addition, McNeilly was told of an officer who frequently left Top Secret documents lying on his bed.

He says there was a lack of adequate security controlling access to Trident submarines:

•The QM sentry (sailor in sentry box at gang plank) not an effective security check, as the sentry routinely lets people pass unchecked.

•MOD Police/Guard Force pass checks and gate checks not thorough. Able to pass without showing face, including when raining. Possible for extra people to get in as part of a group. Lots of missing RN ID cards circulating.

•Electronic gate access with PIN not working.

•No checks on bags being taken onto submarine by sailors or civilians. He was able to leave his bags next to the missiles on his first visit to a submarine.

Sloppy practice

McNeilly described how at times, such as the loading of stores before patrol, the submarine was chaotic. At the end of the patrol both the junior ranks and the senior ranks toilets were flooded and he notes that this was an apt summary of the state of affairs on this deadly nuclear-armed vessel.

Credibility of McNeilly’s report

While it is not possible to confirm many of the points made in McNeilly’s report, there is evidence to substantiate some of his remarks.

He says that Trident missile operators are been given responsibility too quickly without adequate training or experience. The Defence Nuclear Safety Regulator has said that a shortage of Suitably Qualified and Experience Personnel (SQEP) is the primary risk to the Defence Nuclear Programme (DNP). In his 2012/13 report the regulator said, “The ability of the Department to sustain a sufficient number of nuclear suitably competent military and civilian personnel is a long standing issue. It is identified as a significant threat to the safe delivery of the DNP”. It remained the number one issue in the regulator’s 2013/14 report. Changes have been made to training under the Sustainable Submarine Manning Project. Some individuals can be fast tracked through their training and experience.

McNeilly describes how, in the US Navy, two submariners go inside the missile tube, one on top of the other, to remove the DC/AC inverters from the missiles at the end of a patrol. A photo taken on US Navy Trident submarine confirms that this is the case. It shows the leg and foot of one man who is lying inside the missile tube. A second man is on the ladder facing inside, on top of the first man. A third sailor is in the foreground.

McNeilly mentions finding rubbish in the missile compartment, reporting this to superiors and no action being taken. One of the duties of a Missile Technician on a US submarine is to patrol the Missile Compartment looking for hazards like this. UK practice is likely to be the same, at least in theory.

McNeilly describes hearing of a fire in the missile compartment of a Trident submarine. While there is no other public evidence of this incident, the description of problems with a lack of adequate breathing apparatus is consistent with recorded accounts of fires on Royal Navy submarines. His claim that a very small fire can produce a lot of smoke on a submarine is confirmed by other sources.

He describes how it is possible to walk through security barriers without your pass being properly checked. In October 1988 a protestor from Faslane Peace Camp was able to walk through several checkpoints, onto a Polaris submarine and then into the vessel’s Control Room (Herald report). In November 2000 a car-load of tourists accidentally drove into Faslane and was able to get through the checkpoint without any passes (source).

McNeilly quotes CB8890, the instructions for the safety and security of the Trident II D5 strategic weapon system. There is a reference to this manual in a defence safety review. The paragraphs from CB8890 which he quotes are similar to nuclear safety documents which have been released under the Freedom of Information Act.

The submariner’s report suggests that there are a high number of breaches of safety procedures on Trident submarines. This is consistent with an acknowledged rise in nuclear incidents. The number of nuclear safety incidents at Faslane and Coulport rose from 68 in 2012/13 to 105 in 2013/14 (source). Between 2008/09 and 2012/13 there were 316 nuclear safety events, 71 fires and 3,243 “near miss” incidents at Faslane and Coulport (source). There were 44 fires on Royal Navy nuclear submarines between 2009 and 2013 (source).