David was groggy when he woke up, he says. As he looked around, he knew where he was, because he had been there before: an apartment in Dolphin Square, central London. There was something else that was familiar. He was, he says now, wincing, “naked”.

He was 15. His eyes flicker up to the right, reliving those moments in 1982 as if he were back there.

“It’s obvious that something’s not right,” he says. “It’s extremely painful.” Memories from the night before would intrude in flashes – being taken to a restaurant, to a table of men, and being told who they were: politicians, businessmen, senior members of the Church of England. Sometimes other boys his age were there too.

As he looked down there would be another clue. “There’s blood and bodily fluids,” he says. The blood would be his, but the semen was not. He did not know then that it would take more than 30 years to try to find out whose it was.

This is a story about a secret. At its heart is a man who has spent his life searching for justice but kept being denied it, blocked by forces he found hard to understand. Dominating everything, however, was a prolific child abuser with establishment connections whose name has been kept from prominence – until now.

When BuzzFeed News began investigating this story, the details, which pointed to a clutch of paedophiles operating across some of our most powerful institutions, seemed at first too grim and too outrageous to hold up. That was until we started examining the evidence, until the files began to surface, forced into the open through the Data Protection Act and the coroner’s court. These files not only corroborated David’s story, but expanded on it. There were details he wished he had not discovered.

What emerged casts a different light on what we have heard. It reveals how a child from a loving family comes to fall into the hands of powerful predators, how boys like him were brought from the countryside into the capital for sexual exploitation – and what is stacked against them when they come forward. Most surprising is what this case reveals about the police: how despite the prominence now afforded to sexual abuse, they continue to behave in strange and unaccountable ways. Ways that lead to troubling questions.

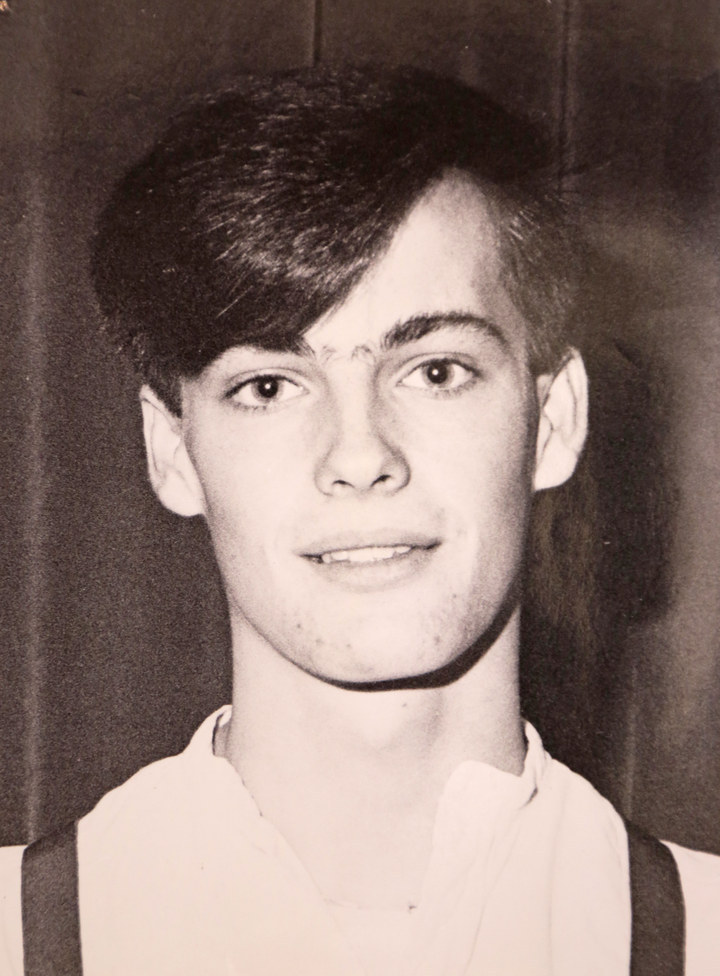

David, now 49, sits upright in an armchair, hands gripped together, revisiting as much as he can. He has decided to forego his right to anonymity – for his real first name and photograph to be used – in the hope that he will, at last, be heard.

We talk in a hotel room for two days. It is the start of the investigation, and as David begins it seems his story is centred on sexual abuse – until something perhaps more startling appears.

There are things he has never said aloud to another person.

David as a teenager outside Dalby House. David

It was a family friend who first took an interest in David. His name was Gordon Dawson.

In spring 1982, two months after turning 15, David moved with his parents and older brothers to Skendleby, a small, picturesque village in rural Lincolnshire. Pretty cottages punctuated the vast fields and farmland stretching out around the village. Dawson’s property came within two fields of their home.

David loved country life. Rarely watching television or reading newspapers, he instead preferred riding and cycling, and was, he says, unworldly for his age. He was very shy and very skinny, with a mass of dark hair atop sharp features.

David’s father had previously had business dealings with Dawson, who was a landed farmer. And so when one day Dawson came to the family home to apologise for his uncle clipping David’s mother’s wing mirror, there was already a connection.

The visit sparked a close friendship between Dawson and David’s parents, enabling him to pop in for a chat several times a week.

“He was big, broad, burly,” says David, with “wraparound” hair, and seemed “jovial, warm, and very clever”. David was aware of the power and wealth Dawson enjoyed.

“He was a big figure locally, a local ombudsman, involved in the church and the local dioceses. Well-respected, well-connected, knew everybody.”

Dawson lived with his wife in Dalby House, a huge country estate set in a thousand acres of land. It was there, amid the hedgerows and woodland of the estate, that Dawson indulged in his favourite pastime: shooting. He liked to include local boys in his pursuit. He would hold days for them called the “Young Boys’ Shoot”, says David, and never expected payment.

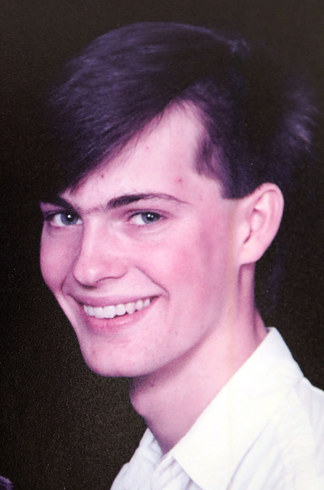

Gordon Dawson in the early 1980s. David

But Dawson offered to give David free one-to-one lessons – an immensely generous offer, it seemed. And so, every couple of days, he would take David out to shoot rabbits. At night they would do so from inside his car. After the shot was fired, Dawson would keep holding on to him.

“I felt uncomfortable, but at the time you don’t know how to compute it,” David says, frowning, as if frustrated with himself. Over the course of one week in early summer 1982 that discomfort escalated.

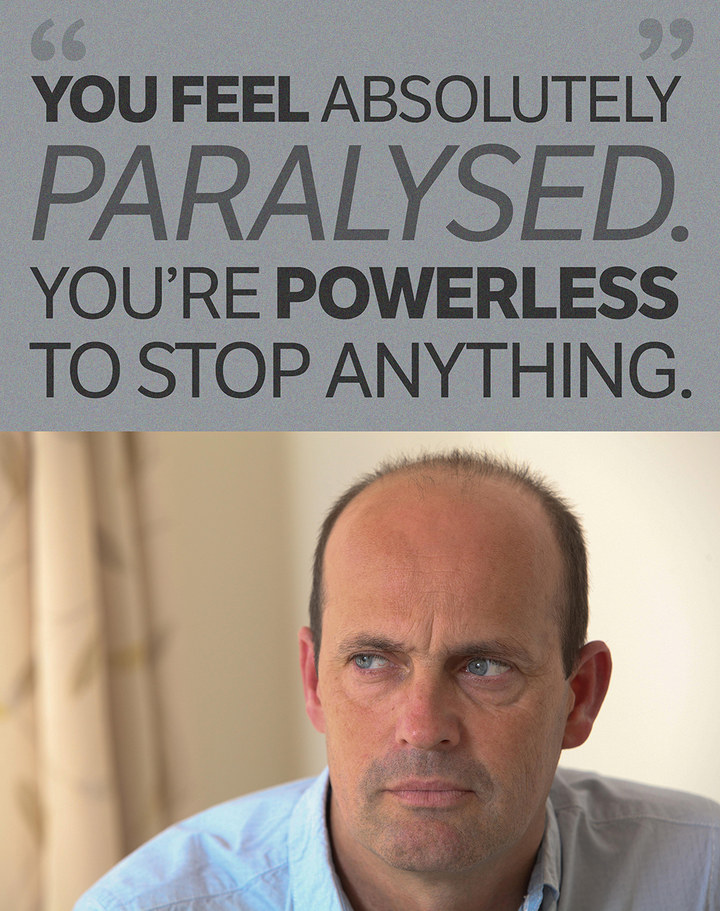

“I remember him putting his hand on my leg. Things would happen gradually over the night – more and more touching… You just freeze. I didn’t have the experience to know what to do. He’s the adult, the same age as my father. By the time he’s got his hand on your crotch you’re just… You can’t breathe. You feel absolutely paralysed. You can’t recognise what’s going on because you don’t understand. You’re powerless to stop anything and he then decides he’s going to put his hand inside…”

David stops, before forcing himself to carry on. “…he’s going to take your zip down and then it just happens. You just want it over as quick as possible.”

In the darkness, surrounded by private land, Dawson, says David, raped him. He didn’t know at the time what the word was for what had happened. “I didn’t understand. Now I look back and that was absolutely what it was.” David looks up intently, as if wanting to emphasise what took place there.

“I could show you on the map where the first time happened,” he says. He remembers coming home afterwards. “I didn’t know what to say to my parents. I didn’t want to upset them.”

Rebecca Hendin / SWNS for BuzzFeed News

Dawson was charming and generous, leading David’s parents to believe their neighbour was a good friend. They had no idea what he was capable of.

David begins to set out the pattern of behaviour Dawson was establishing – “he wasn’t that bothered about you touching him, it was all about him using you” – when two aspects emerge that provide a vital clue to the later events in London. Dawson would never ejaculate, says David, and had such a small penis that being raped by him did not cause David bleeding, significant pain, or injury.

Desperate to get away from Dawson, David told his parents he hated his new school, that he was struggling there, and complained so vehemently that they eventually agreed to let him return to his old school in Cambridgeshire, a two-hour drive away. It meant staying with old friends during the week. “I thought I was removing myself from the situation,” he says. It would prove catastrophic.

Dawson offered to pick him up on Friday nights. At first this meant stopping in country lanes on the way back to Lincolnshire. “He would turn off the engine and say, ‘Right,’ and that was it – you would think, ‘Get it over with,’” David says. But shortly afterwards, in autumn 1982, Dawson made David’s parents another offer.

“He would say, ‘I’ll take David to London for the weekend and we’ll go to the theatre!’ I couldn’t get out of it – my parents would say it’d be great.”

By this stage, says David, he was becoming increasingly withdrawn. But how was he feeling? After hours of talking, remaining as calm and controlled as possible, David suddenly doubles over.

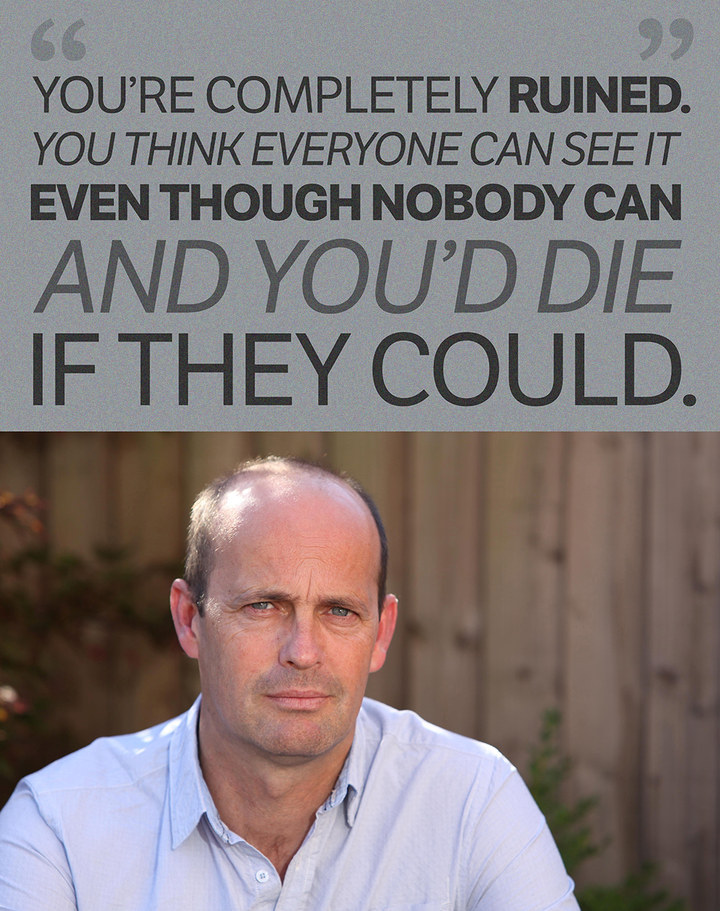

“Empty,” he says, his voice strangled as he rubs tears away and attempts to carry on. “That’s a horrible thing…” he whispers, “…a horrible thing…” He apologises and tries to regain composure. “Empty because there’s nothing left: It’s a shell. You’re completely ruined. You think everyone can see it, even though nobody can and you’d die if they could.”

Rebecca Hendin / SWNS for BuzzFeed News

David remembers the first time Dawson took him to Dolphin Square, a vast 1930s complex in Pimlico, just a few streets from Westminster. “To me it was very grand,” he says. The 15-year-old, unused to such a venue, thought it was a hotel, and would later refer to it as such in his police statement.

He remembers an underground car park from where they would walk up steps on to street level, to an arcade of shops, and then up more staircases and corridors to reach a flat. (Years later, he says, a family friend told him it was owned by Dawson and two other men.)

David can still picture the inside: “Very bijoux, cottage-y, magnolia walls, but the curtains were quite pretty – yellows, blues, and greens – and that theme ran throughout.”

On these trips to London, they would go shopping. Some of the gifts – photos, paintings, a briefcase – would end up in police possession. Traumatised by the memories, David is unsure of the exact number of times he was taken to Dolphin Square, but says his mother has told him it was “at least 10 times”. There was somewhere else Dawson took David, he says.

“We would go to church meetings at the [General] Synod.” David would sit in, bored and unaware of Dawson’s precise role there. But as they walked round Dolphin Square, says David, Dawson would tell him that people from the Synod also had flats there.

In the corridors of the square, they would bump into other residents, he says – suited men who knew Dawson and would stop to chat.

Dolphin Square Carl Court / Getty Images

“It was all very jolly and familiar. He was very well-regarded. And I knew that lots of MPs lived there, and people from the church, because he told me.” (Reports suggest over 100 MPs have had flats in the square.)

In the evenings Dawson would take him to restaurants – most frequently to Motcombs, an upscale establishment in Belgravia – where a table of men would be waiting.

“He would tell me there were people there [at the table] who had big military careers, people from the church – he would say that some are from the Synod – and then [also] MPs. There always seemed to be a parliament connection. They’d always be talking about something that had come up that day in the House [of Commons].” David would be introduced to them but, still only 15, would never be told their names.

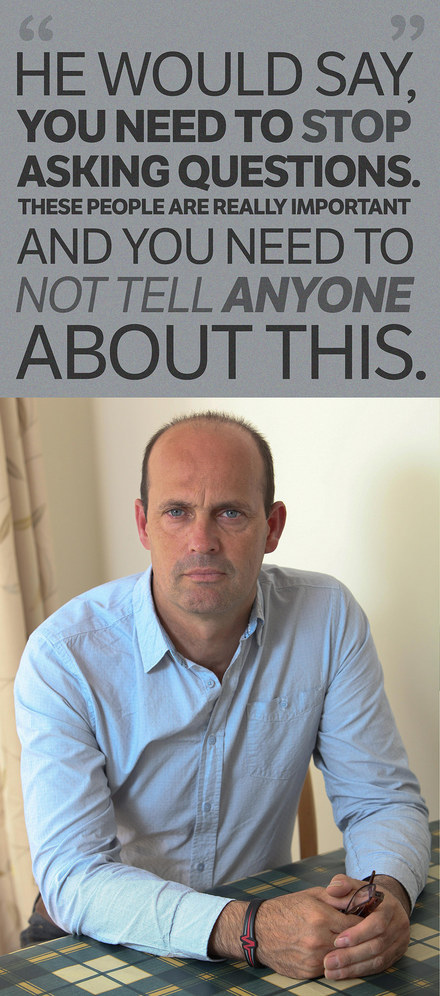

“He [Dawson] was very cut and dried about that. He would say, ‘You need to stop asking so many questions. You just need to remember these people are really important and you need to not tell anyone about this.’”

As they ate, Dawson would give David red wine, he says.

“Sometimes at the dinners there was someone else my age,” he says – boys accompanying other men there. They wouldn’t be sat together.

The problem for David is that his memories cut out before the end of the evenings.

“I cannot remember leaving a restaurant,” he says, frustrated again. “[It] becomes very hazy, like you disappear, drift off, and then suddenly it’s the next day. I knew things had happened by the time I woke up, because it’s one thing Gordon having anal sex with you because he was very small and all the times he abused me he never climaxed.” Waking up in Dolphin Square, however, was different. He revisits the scene in his mind, his voice tightening.

“If I was really sore, or it’d been particularly bad, then I would be worried,” he says. His response by then was practical. “You’ve got to tidy yourself up. I was really upset if there was a mess on the sheets, because I’d think, ‘Oh god, someone’s going to know.’ So I used to take the sheets off the bed before we left and put them in the bin.” He stops for a moment, suddenly seeing those times with the perspective of an adult.

Rebecca Hendin / SWNS for BuzzFeed News

“That’s when you’re completely broken.”

Sometimes, on waking, he would hear male voices in the flat – men who would leave soon after. After disposing of the sheets, David would have a bath as soon as he could, but Dawson, he says, would often join him: “I said no on many occasions but it didn’t work.”

On the way back to Lincolnshire, “Gordon would say, ‘No one’s going to believe about Dolphin Square,’ and I didn’t really understand what he meant. It’s not until now that I understand the gravitas of it. Then, I thought that referred to the fact that physically [the abuse] had been quite a big event. What he was referring to, more than likely, was the people.”

The gaps in David’s memories follow a set pattern: being in restaurants, and then nothing until he wakes up in Dolphin Square. An acquaintance has since suggested to David that he might have been drugged, but David doesn’t know.

“I know I was abused by Gordon, raped by him,” he says. “And there were certainly other people involved, there had to be, because of the after-effects and physical ramifications, but I don’t know who.” David is certain about this: After being raped in Lincolnshire, he would not bleed, be in pain, or have semen on him – a distinct difference to waking up in London.

Another memory taunts David. In addition to the trips to Dolphin Square, Dawson took David shooting on a few occasions to Blickling Estate, a stately home with vast grounds in Norfolk. While staying in local guesthouses, Dawson would abuse David again, he says.

Blickling Hall ThinkStock

One night in the room they were sharing, “I remember something getting going, I remember there being more than one person – it wasn’t just Gordon, there were two others. I remember someone’s face being so…” he gestures a few inches away from his face. “I can remember being forced into the bed, trying to see, and this chap’s face is here and he had white/grey hair. I remember his hair because he had a lot of it.”

From the age of 17, after more than two years in Dawson’s grip, David finally began to get away, by refusing to see him or go to London. By then, and despite an unusually high IQ, David had dropped out of school. He retreated from people – “you’re safe on your own” – spending time instead with his horses. What was going through his mind during that period?

“That I might be finished… That my life might be over…” He stops and breathes for a moment. “…but it didn’t mean it had to be wasted.” David vowed that somehow he would seek justice and find a way to use what happened to help others. The determination to do so would keep him going for years, fuelling everything that was to unfold.

David tried to build a life. He had a relationship and told his partner what had happened to him. He became a racehorse trainer. But all through the 1980s and 1990s he lived with the memories of Gordon Dawson and Dolphin Square. In 1996, he disclosed what happened to a woman who’d lived next door to him growing up, who also knew Dawson, and whose later police statement has been seen by BuzzFeed News.

“Elizabeth’s first words were, ‘I wondered how long it was going to be before you told me.’ Her husband used to say, ‘Why does that boy come down here talking to you?’ And she used to say to him, ‘Because he’s got something to tell me and one day he will.’”

It wouldn’t only be Elizabeth David would tell. After more than 20 years carrying shame and memories he could not bear, David decided to fulfil the promise he’d made to himself two decades earlier. Although fearful of what would happen, and having long attended a support group for abuse survivors, David finally contacted the police in February 2007. He thought he was doing the right thing.

David

David

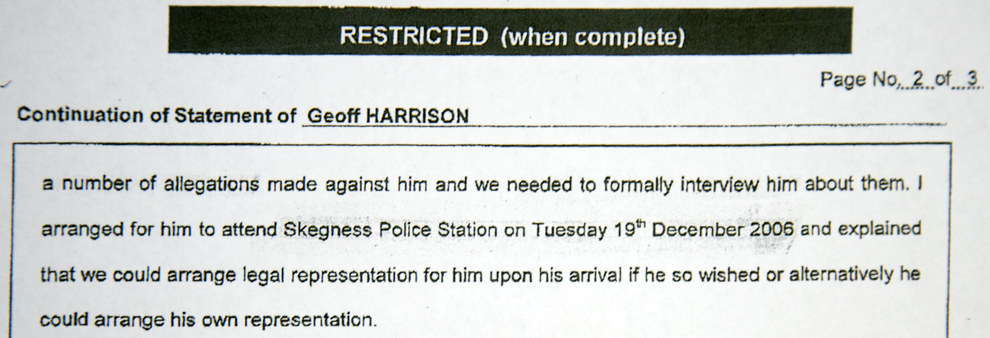

An investigating officer, Sergeant Geoff Harrison, came to David’s house to conduct a full interview. The interview would form the basis of David’s police statement, seen by BuzzFeed News, in which he describes, among other things, being raped by Dawson in Dolphin Square. At the time the flats were not publicly linked with sexual abuse, and Harrison, says David, was more concerned with the events in Lincolnshire.

“I said, ‘Am I the only one?’ He [Harrison] almost laughed. He said, ‘No, this is huge. It’ll be the biggest case this country has ever seen.” David says the sergeant informed him the police had been investigating Dawson for nine years; that “over 20 people had come forward”.

“The police believed Dawson had been an active paedophile for 45 years,” he adds. “Geoff told us to expect heavy media intrusion should [the case] go the way they would hope.”

It did not. Instead, a series of strange events began to occur that has baffled those who have looked at this case.

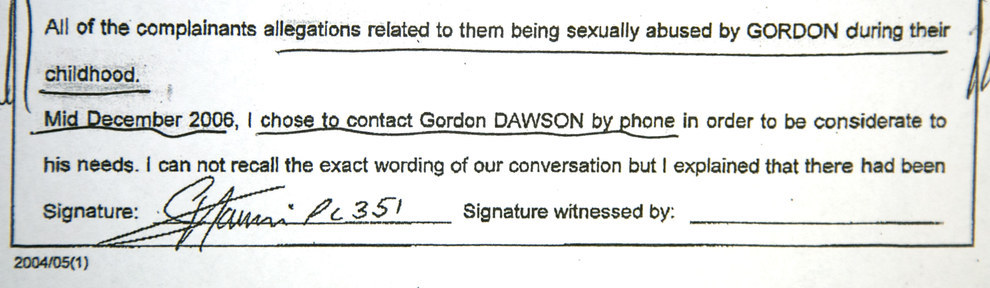

What transpired, according to police documents obtained by BuzzFeed News, is that Harrison had first arrested and questioned Dawson in December 2006, after interviewing five people alleging abuse since that October alone. Dawson denied everything.

But when David came forward two months later, having heard a rumour about accusations being made, the police suddenly seemed galvanised into further action, he says, and told him that with his testimony they would rearrest Dawson.

Although heartened by this, David had a concern. Dawson kept a large collection of guns in his house, so David says he told the police this and asked them to remove the weapons before they rearrested him. (Officers can apply to the firearms department within their force to approve this.)

“I said it again and again, ‘You’ve got to do this, you can’t risk anything happening.’ When I went to sign my statement I said, ‘Any progress?’ And Geoff [Harrison] said, ‘No, we’ve put in a request but unfortunately it was denied. They’ve looked at it and they’ve deemed that he’s not a risk.” David cannot understand how someone in Dawson’s position could not be considered a risk.

Leading criminal lawyer Nigel Richardson, the author of a textbook on investigating sexual offences, tells BuzzFeed News: “These days the police are very careful to at least go through the motions of making sure anyone arrested for a sexual offence is not a danger to themselves.”

But it was what happened the day after David signed his statement that would form the centre of his criticisms of police conduct.

Sgt Harrison rang Dawson to warn him he was going to be rearrested.

The details of the call are confirmed in a signed statement from Harrison at the time, which BuzzFeed News has obtained. The document reveals something else: Harrison did the same thing before arresting Dawson for the first time in December, “in order to be considerate to his needs”.

Matt Tucker / BuzzFeed

Matt Tucker / BuzzFeed

This is not standard procedure, says Richardson, the criminal lawyer: “For an allegation of this seriousness it’s pretty unusual. Because the police want the element of surprise – they want to be able to capture any evidence. They want those things seized rather than hidden.”

On the second occasion that Harrison warned Dawson of his impending arrest the call took place at 4:40pm on 23 March 2007. The sergeant arranged a day convenient for Dawson to come in to the police station the following week, and informed him that he would be arrested and questioned. Harrison’s statement ends: “Dawson did not give me any indication for any cause for concern of his welfare or safety.”

“I just don’t understand why they would ring,” says David. “Why risk it?” But there was another aspect to the phone call that would later stagger him.

David says Harrison told Dawson who the new witness was: that it was David who had come forward. David adds that he knows this because, he says, the sergeant rang him after phoning Dawson, and told David he’d disclosed to Dawson the identity of the latest accuser.

Again, Richardson, the criminal lawyer, is “very surprised” by this: “The police don’t want to give people too much opportunity to think things through in their head, and at that stage they had no protection for the complainant.”

David says Harrison told him that Dawson, after being informed who had come forward, “did not react well”. In Harrison’s statement he does not mention informing the suspect from whom the new allegations came. However, a letter from David to Lincolnshire police in 2007 reiterates that he had been told Dawson was informed who it was.

Later that day – 23 March 2007 – a local friend phoned David.

“He said, ‘Have you heard?’”

David guessed.

At 6pm Dawson’s wife found his body alongside a rifle in a patch of woodland on their estate. Blood surrounded Dawson’s face and head. The postmortem examination, seen by BuzzFeed News, revealed a single shot had entered his skull on the right side of his head. There was no sign anyone else was involved.

The police, says David, did not contact him to inform him Dawson had died.

For 25 years, David had kept going, sustained by the belief that somehow Dawson would be brought to account.

“He had won,” says David. “He doesn’t ever have to face questions. He’s got away with it.” The case was closed. Harrison, he says, stopped returning his calls.

David complained to the police. He says he asked them, rhetorically, if they warn drug dealers when they are about to be arrested. Richardson, the criminal solicitor, tells BuzzFeed News: “The police simply wouldn’t do that in a drugs case.”

But when the case was referred to the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC), it was sent back. Following a freedom of information request by BuzzFeed News, the IPCC said, “This was not a matter that warranted our involvement and we were content it could instead be handled by the Lincolnshire police.”

Because the IPCC refused to look into it, a local chief inspector named Tom Bell, from Lincolnshire police’s professional standards department, was tasked with investigating the conduct of officers from his own force.

On the day of the inquest in May 2007, which David attended, there were several developments.

A member of David’s family, who accompanied him there, told BuzzFeed News there was something interesting about the man representing the Dawson family – a man named Philip Odling: that Odling was not only a close friend of the Dawson family but also an old friend of Sgt Harrison.

David wonders whether, if this is true, it was right for the officer investigating a suspected serial child abuser to have had a close friend in common with him. When BuzzFeed News asked Lincolnshire police to comment on this, they refused to respond.

The coroner recorded an open verdict. No suicide note had been left, and Dawson’s wife’s statement to the coroner, also seen by BuzzFeed News, reveals: “Although my husband was low he was not taking any medication for it and everything seemed to be normal.” However, it is believed Dawson took his own life.

But there was more. Outside the inquest, says David, Chief Inspector Bell – who was conducting the internal police investigation – tapped David on the shoulder and introduced himself.

“He said, ‘Can we have a chat?’ It appears you might have a case. I’ve spoken to the head of firearms, who was completely unaware of the situation, and of Gordon Dawson.’” As far as Bell was concerned, says David, no request to remove the guns had been made.

This left David confused and keen to find out what happened – it would mean that despite the potential risk of Dawson turning a gun on himself or others, Harrison did nothing to prevent it and instead told Dawson they were coming for him. BuzzFeed News has asked Lincolnshire police, Harrison, and Bell to explain this but they have declined to do so.

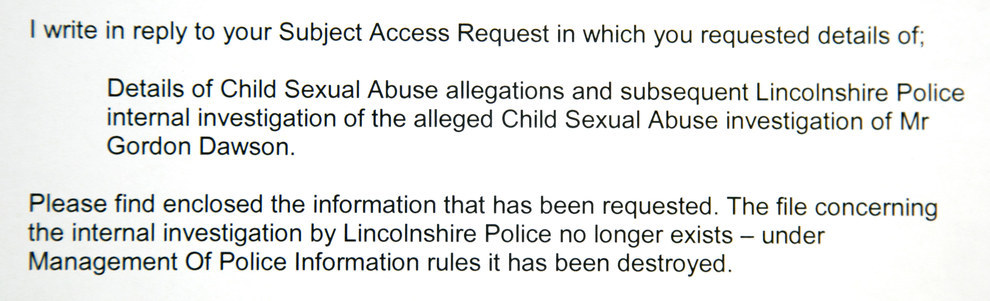

“He [Bell] said he would be back in touch,” says David. But, he adds, “I never saw a report.” BuzzFeed News made a freedom of information request to Lincolnshire police to retrieve Bell’s report from his internal investigation. It was denied. David, however, using the Data Protection Act, requested all the files of the Dawson case from Lincolnshire police.

The response revealed what happened to Bell’s report: “It has been destroyed.” The letter stated this was “under Management of Police Information rules”, although no specific explanation was offered. Nor did the letter state when the file was destroyed.

Matt Tucker / BuzzFeed

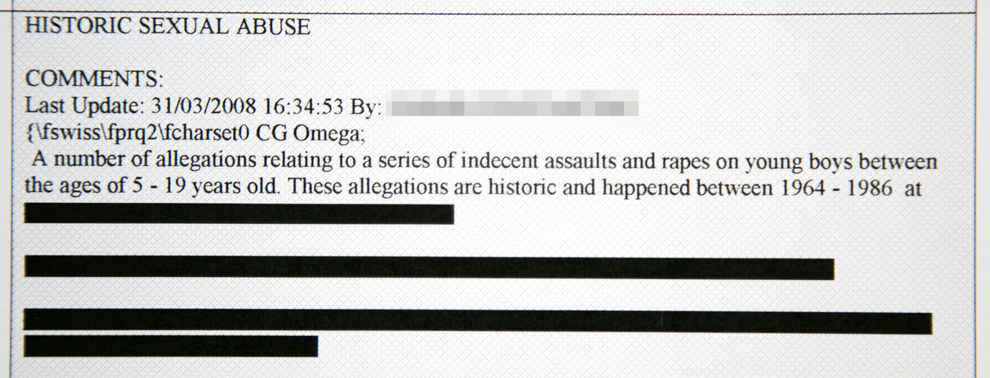

Some of the files regarding the original police investigation were made available, however. Although largely redacted, what remained startled David: Some of the allegations against Dawson, which stretch back to 1964, included the sexual abuse of boys as young as 5.

The few lines in the files that are still discernible – the odd quote from the police interview with Dawson in December 2006, for example – are all familiar: boys in his car, country lanes, shooting rabbits, trousers undone. Two capitalised words jump out in the police notes: MODUS OPERANDI.

Matt Tucker / BuzzFeed

In March 2015, aware that the Metropolitan police had set up various operational teams to investigate allegations of past sexual abuse by public figures, David decided to try to find out what happened to him one more time – and to discover what took place during the Lincolnshire police investigation. It was just three months after the Met had appealed to the public to come forward with information about Dolphin Square.

David attended an interview with two officers working within Operation Fairbank, the investigation set up to gather evidence of historical sexual abuse by politicians. Many questions remained for David: Why was Dawson forewarned of his arrest? Why were firearms not removed from his house first? Why did the case close immediately after Dawson’s death? And why was he not shown the report from the internal investigation?

But there were other questions, too: Why was the information about Dolphin Square David had given to Lincolnshire police in 2007 seemingly not investigated nor passed to the Metropolitan police? Why were many of Dawson’s friends, including two men who, David had been told, co-owned the flat with Dawson in Dolphin Square, not interviewed? Why has there never been any attempt to find out who sat with him at those restaurants?

David left the interview with the Metropolitan police officers full of optimism.

“They were very animated,” he says. “[By] the firearms issues, the investigation that never went anywhere, the fact I was never informed Dawson had died and that a 9-year case just died. They said, ‘You’re right to be concerned.’ They were very keen to get stuff from Lincolnshire police. They said they would be speaking with Geoff Harrison, requesting the file, and they felt this case had to be reopened.”

A few days later, one of the officers sent an email to David, which he forwarded to BuzzFeed News along with all correspondence between him and the Metropolitan police.

“There is nothing further for us to investigate here,” it said. “The information that we discussed doesn’t fall within the remit of [Operation] Fairbank or the Metropolitan Police.”

Shocked but still determined to find the truth, David emailed back setting out all of his concerns. Towards the end of the email David made a plea:

“I was systematically abused and raped as a child by men at Dolphin Square. All I want is some credible answers.”

Keystone / Getty Images

Getty

Five days later, on 25 March 2015, Detective Sergeant James Townly, a senior officer from Operation Fairbank, responded to David’s questions. We read the email together in the hotel room.

Because David does not know exactly who the men at the restaurants were, “this is not sufficient for a crime report”, writes Townly.

But David does know the names of the two men he was told co-owned the Dolphin Square flat with Dawson. BuzzFeed News has discovered that one of these men is still alive and that David had supplied his name to the Metropolitan police. But according to Townly, because this name, and others David has given them who may have information, are not already known to the Met, it won’t investigate those either.

“Every investigation carried out by [the] Operation Fairbank team is examined for links to previous reports or intelligence already held,” says the email, adding that Dawson and the two other men “are not names that have been mentioned to us as part of Operation Fairbank”.

David is aghast as he reads this and switches into satire. “Bring us the pictures, the videos, and the signed statements and we might look into it,” he mocks.

Townly continues: “It is not feasible for the police to investigate every potential or convicted paedophile for links to others. In an ideal world we would very much like to identify all offenders and identify their links to other paedophiles and networks [but] sadly that does not happen.”

But criminal lawyer Nigel Richardson is perplexed by this. “You would think they would want to track down links if they are pointed out,” he says. “I can’t see why they wouldn’t want to do that, if they’ve got names and potential links. It seems to me it’s part of their duty to carry out an investigation into those, at least to rule them out.”

The police, adds David, “are not doing their job”.

In a further point that may surprise those who have followed the allegations of child abuse surrounding Dolphin Square, Townly states: “Dolphin Square as a venue is not being investigated. There are in excess of 1,000 flats at the square all of which could at one point on [sic] other in time being venues for sexual abuse.”

Townly concludes: “Operation Fairbank is responsible for investigating allegations of child abuse involving MPs” and “uncovering allegations of paedophile rings which primarily involve MPs”, adding, “The allegations you made previously to Lincolnshire and some of what you have said recently involve neither so there is nothing for the Operation Fairbank team to investigate.”

Townly then attempted to recall the email – some email systems allow the user to stop the message before the recipient can open it. But David had already saved the email. He sits staring at it.

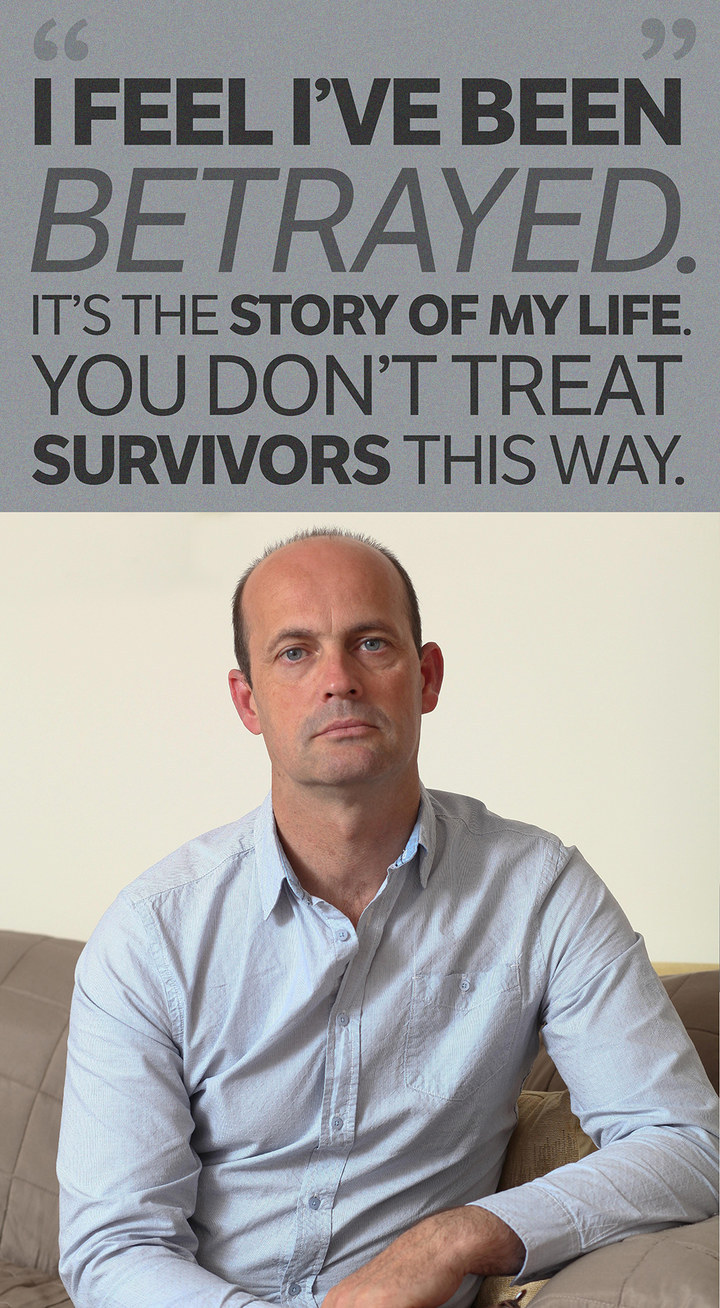

“I feel I’ve been betrayed,” he says, softly. “It is the story of my life. You don’t treat survivors this way – the police have still got a lot to learn.”

When the email from Townly arrived, in March 2015, it was, says David, devastating: “The worst time of my life. The fight I had to control the anger was the hardest fight I’d ever had.” He looks down. “I was concerned for my own welfare.”

Rebecca Hendin / SWNS for BuzzFeed News

When approached by BuzzFeed News, a spokesperson for the Metropolitan police said: “Experienced officers working to Detective Sergeant Townly in SOECA [the Met’s Sexual Offences, Exploitation, & Child Abuse division] did review the material in this case, including speaking with relevant people. This work was subsequently reviewed by DS Townly. In the absence of new lines of enquiry, substantive allegations made, or further new witnesses, the matter remains closed.”

David is aghast. Why, he wonders, do the police not try to find out who else abused him and who was at those restaurants? Why can’t they at least speak to the people whose names he gave them? What else could be going on here?

But for David this was at least a response. When BuzzFeed News puts his allegations and questions to Lincolnshire police, a spokesperson replies 11 days after the deadline: “We will not be responding.” Tom Bell, now retired, also did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for comment.

As BuzzFeed News’ two-day-long interview with David comes to an end, he falls silent. His arms hang by his side. He looks suddenly childlike and alone. As he sits in the hotel room retreating into himself, the image conjures something he said the previous day: “I feel that I am still 15 years old.”

David as a teenager. David

It invokes too a line from the personal statement he gave to Lincolnshire police in 2006 – a picture of the impact of everything that has happened:

“I went for years without touching anybody or shaking anybody’s hand.”

David has contemplated suicide several times. To live without justice is unbearable, he says. He likens it to an incurable cancer. More than 30 years on, as public focus shifts from survivors to celebrities, and with widespread criticisms of the Met, David still does not know who, apart from Dawson, was responsible.

Before we leave, he turns for a moment in his chair to gaze out the window. The sun blazes down on the people below: shoppers, office workers, mothers with buggies.

“People talk about truth, honesty, and justice as if they are sweets you give away,” he says, suddenly still. “But they are the three most important things you will ever have.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

We welcome all points of view but do not publish malicious comments. We would love to hear from you if you want to e-mail us with tips, information or just chat e-mail talkingtous@hotmail.co.uk